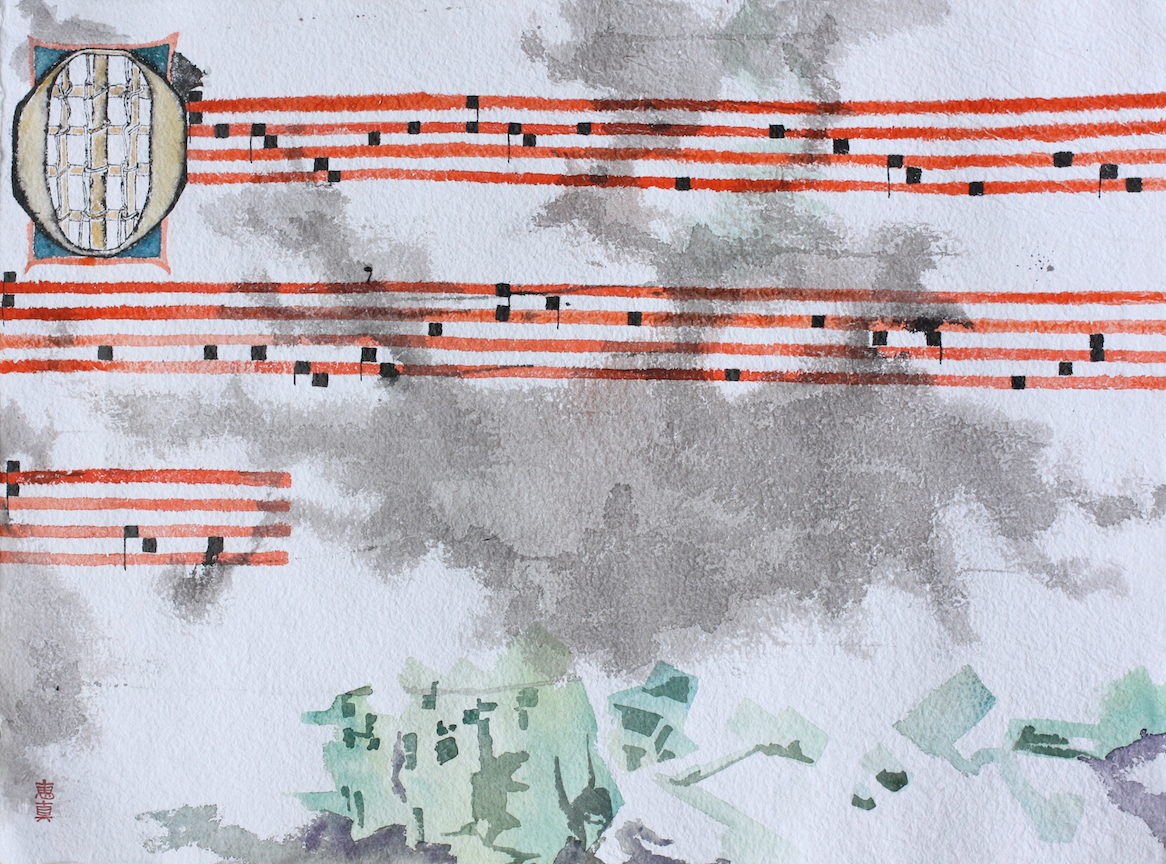

I started this Unzen series after reading about a music historian’s discovery of a 16th-century Spanish Gregorian chant…in Japan.

The historian was thrilled with the findings, and I could relate with his excitement from when I finally put together pieces of a complex historical puzzle after much research during grad school. He wrote that the survival of the chant until now in the underground Japanese church was nothing less than a miracle. Even in Europe in the 20th century, the piece only existed on paper in the archives of Madrid.

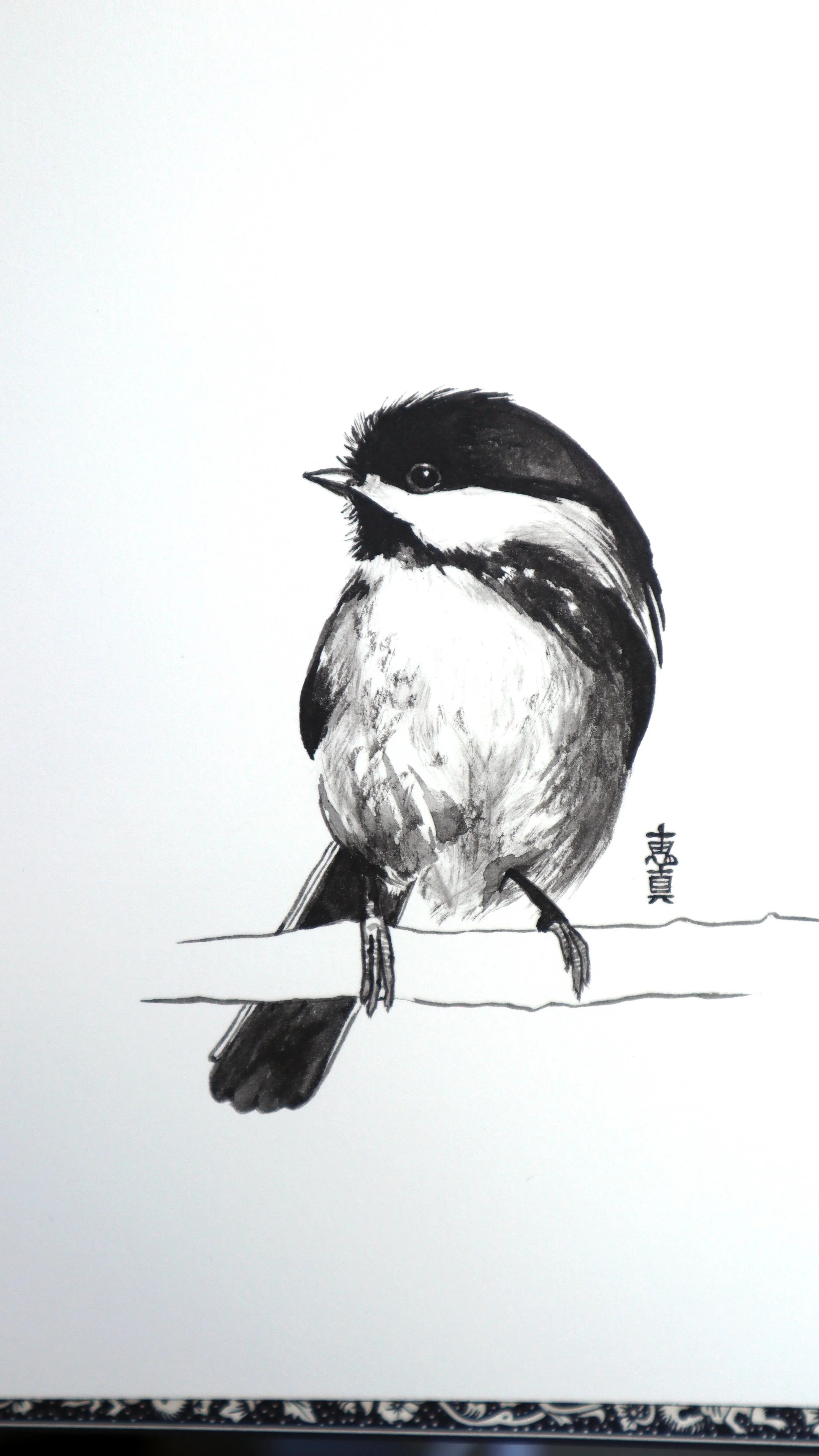

On one hand, it’s a story of hope that the underground church continued to survive for over 200 years, along with this music. On the other hand, the reality of what kept them underground is haunting. It reminded me again of the interdependence of hope and suffering.

Unzen is known for hot springs as well as its history as a place where Christians were tortured. This is where the movie Silence opens. (Movie is a must-see! This Huffington Post article is concise and thoughtful, written by an expert on this period who kindly introduced me to many scholars while researching for my thesis). At the hot springs, people were continuously splashed with boiling water, but kept alive to continue the torture for days. Some recanted, some did not.

I visited the Unzen hot springs a few years ago (and took the photo above) to experience the scene in person. If I hadn’t known of the history, it would have been a beautiful place to enjoy. I wrestled with wanting to call the place beautiful, but also didn't want to because of its past. The evil use of the hot springs doesn’t remove the intrinsic beauty, but it changes it. Similarly, the miraculous story of the underground church is full of hope on one hand, paired with sorrow because of the reality those Christians faced for hundreds of years.

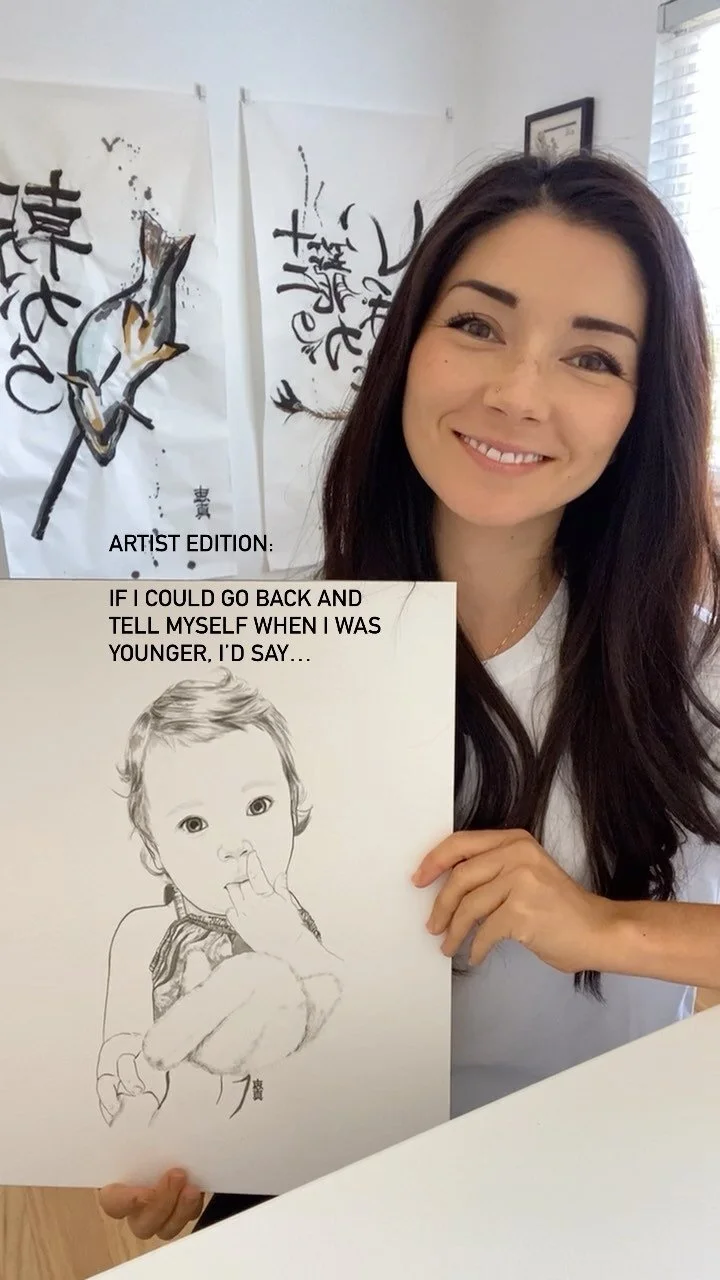

I often try to categorize things as good or evil, useful or wasteful, beautiful or plain, but history reminds me that it’s not that clear.

The gray zone includes suffering. I wish it were avoidable, but avoiding also means missing all the good that results. These stories of hope wouldn't exist without the pain.

I hold to the same faith as these people hundreds of years ago, and I continue to ask myself how I would have responded. Martyrdom sounds noble, but what if it means your entire family and all neighbors would be held responsible and killed because of you. Is it "the right thing to do" to get everyone else killed?

The notes in these pieces remind me of their faith that carried on, much like the 16th century Spanish chant. By the time the music historian heard the music in the 20th century, the piece was barely recognizable from its original form and sounded far more like a Buddhist chant. Yet its core structure and notes were undeniable. The Japanese Catholic faith from the 17th century was expressed differently than contemporary Christianity. They didn’t have any resources—no priest or teacher, no Bible, no church—but they somehow kept on.

I'm grateful for the same hope we can hold to now:

Praise be to the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ! In his great mercy he has given us new birth into a living hope through the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead, and into an inheritance that can never perish, spoil or fade. This inheritance is kept in heaven for you, who through faith are shielded by God’s power until the coming of the salvation that is ready to be revealed in the last time. In all this you greatly rejoice, though now for a little while you may have had to suffer grief in all kinds of trials. [1 Peter 1:3-6]

More to come on the each of the pieces in this series.